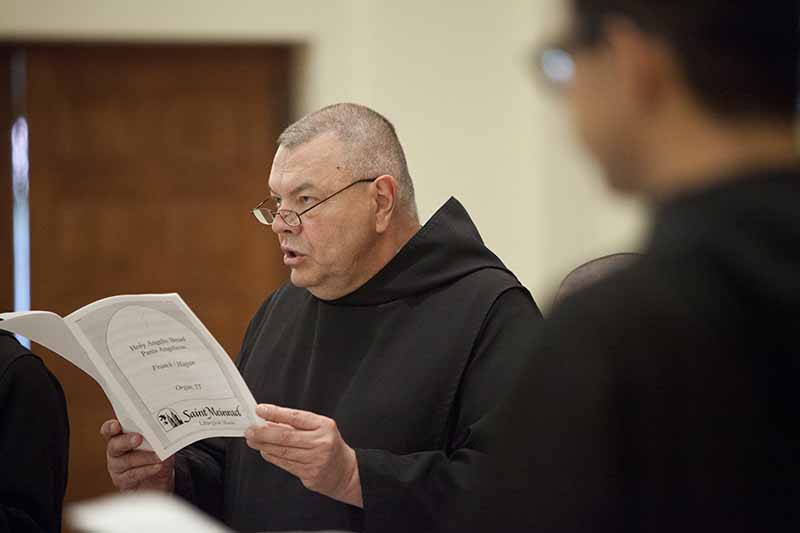

Stability: A Vow to “Stay Put”

Fr. Adrian Burke, OSB

Thursday, August 31, 2023

We live in an incredibly mobile society. The average young American will change jobs more than three times within their first decade in the workforce. In fact, Forbes reports that 91% of Millennials (adults born between 1977 and 1997) expect to stay in a job for less than three years, and the average adult overall will hold a particular job for only 4.4 years over his or her working life.

We also live in a high-tech world that enables, if not encourages, more mobility - 90% of adults own a cell phone, 60% a smartphone and other technologies that allow adults to carry their office in their pocket or briefcase. As a result, Americans are living their lives "on the run."

Not every job change means uprooting home, but about six in 10 adults (63%) have moved to a new community at least once in their lives (2010 Pew Research on American Mobility).

Advances in technologies make life more convenient in many ways. I can get my email virtually any time or any place, delivered to my pocket via my iPhone, and I can access the Internet and retrieve information from my phone almost instantaneously via Google.

But along with the convenience comes the added pressures of having to meet what can be weighty demands for instantaneous communication, pressure we often put on ourselves when we think we have to respond to emails or text messages as soon as we receive them. This constant "need" to stay connected and up to speed, or even entertained, can keep us distracted from our work, or from relationships, that need presence and attention.

One of the vows monks make when we commit ourselves to living the monastic way of life is called "stability," sometimes rendered "stability of place." In his Rule for monks, St. Benedict speaks of the monastery as a "workshop."

In the fourth chapter of the Rule, titled "The Tools for Good Works," he presents what is basically a lengthy list consisting of commandments from the Old Testament, Gospel-imperatives that Jesus teaches to his disciples, and several disciplines and attitudes Christians should cultivate regarding their relationships with God, their fellow monks and themselves.

Most are scriptural, but there are also teachings that come from the monastic tradition itself - moral and spiritual precepts that monks are expected to observe in the "workshop where we are to toil faithfully at all these tasks in the enclosure of the monastery and stability in the community." (RB 4.78)

Stability protects the monk from the flux of society and roots him in a particular monastic household by mutual commitments of support. Stability is more important than ever in a society such as our own that stresses constant movement - either literal, physical mobility, or perhaps more prevalent, the mental gymnastics demanded by a constant barrage on our attention from many directions at once.

The vow of stability roots us in a particular place - this monastery - and commits the monk to a specific group of people, a family of relationships that require care if they're to develop beyond the merely superficial. In this technological age, stability may also mean a commitment to limit distractions caused by technologies needed for work, like computers, cell phones, tablets, etc.

Perhaps, given the reality of high-tech demands on our attention, we can exercise a new expression of stability by putting a premium on concrete, physical presence and "high-touch/low-tech" communication that goes deeper than texting, "tweeting" or Facebook messaging. That would demand something more of us, something more human perhaps!

In 2014-2015, the monks were busy with what we coined "The Move" from our monastery into a temporary home in St. Anselm Hall while our monastery underwent a facilities upgrade. In the process, the monastic community experienced a bit of what it feels like to be uprooted.

Of course, we only moved from north of the Abbey Church to the south side, but my own experience of having to move my home into a new space has certainly involved a certain amount of stress. Adapting to the new spaces and routines caused in me a deeper appreciation for stability, especially at the literal level.

For the monk, his "cell," his private room in the monastic enclosure, is the primary place where he is to encounter God in personal prayer, and as such, it is a cherished and sacred place where he opens his heart to God.

He is also expected to become skilled with "the tools of good works" within the monastic enclosure, where he engages Christ in the community of brothers through service, fellowship and sharing life in community. Our house is our home, but stability demands we continue to faithfully do these things even in our temporary spaces, which we always do, you can rest assured.

It's been my belief that the monastic value of stability has very much seeped into our broader Saint Meinrad Archabbey culture. Our co-workers are anything but "average" in the quality of their commitment to Saint Meinrad as a place of work. The average Saint Meinrad co-worker is employed here around 17 years, an impressive commitment for which we are grateful.

May God continue to grace and bless them and their families, and give success to the work of their hands!