Personal Accountability

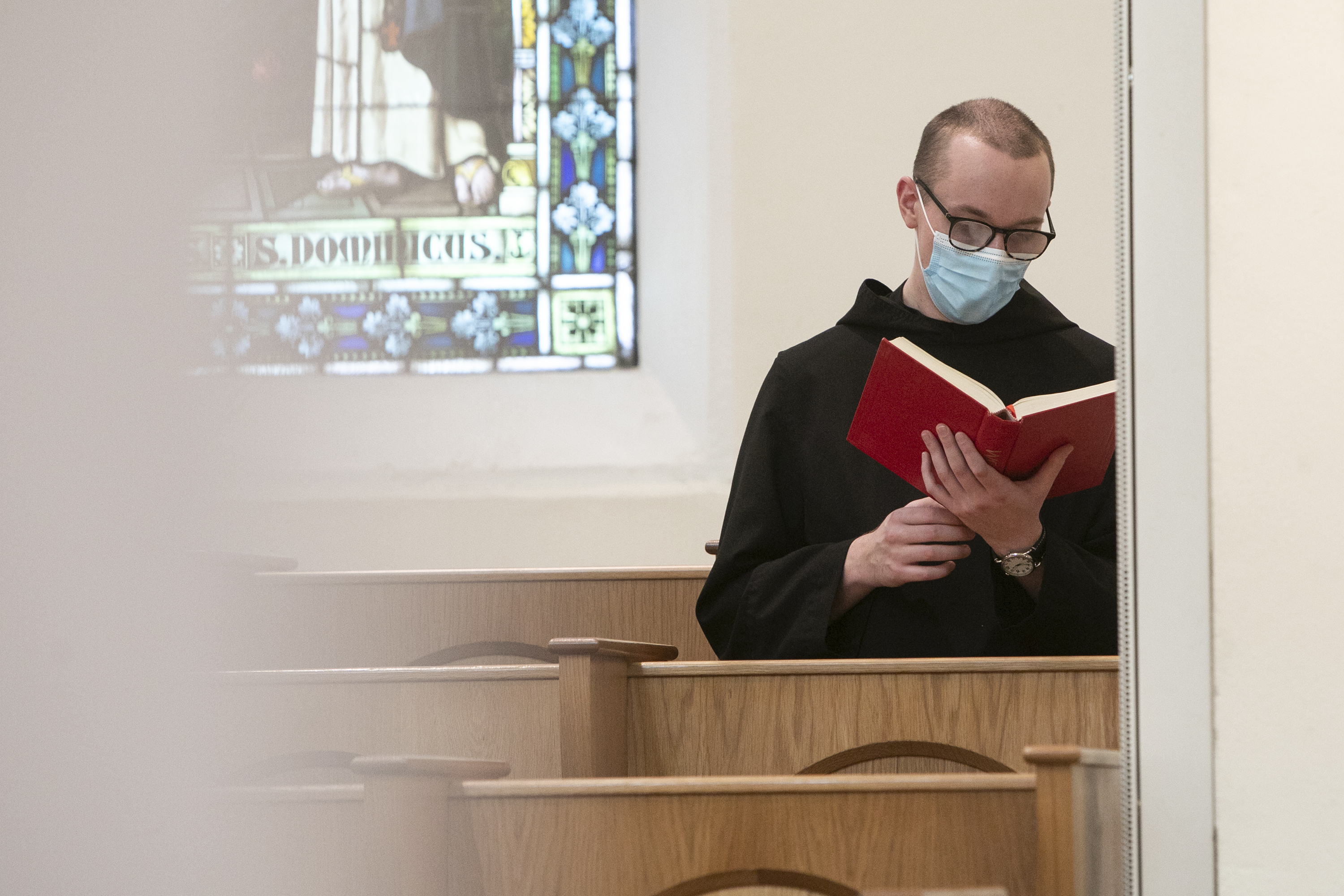

Fr. Adrian Burke, OSB

Thursday, July 29, 2021

"If a monk commits a fault while at any work ... [he must at once] of his own accord admit his fault and make satisfaction."

Rule of St. Benedict: Chapter 46.1:3

There is a small section of the Rule of St. Benedict (RB 44-46) that deals with "satisfaction for faults" committed by monks. "Faults" are personal mistakes that in some way unsettle the flow of the liturgy, disrupt work, break the silence at meals in the refectory, or damage something of value.

Faults mentioned by Benedict involve those committed in the church (RB 45), those committed at work or in the house (RB 46), such as breaking something "in the kitchen, the storeroom, while serving, in the bakery, the garden, in any craft or anywhere else" (46.1-2).

Such errors are "faults" insofar as they can happen when one isn't being careful, or through negligence, or it may be that one lacks dexterity and might be described as a bit clumsy. Faults of this nature are not deliberate, and they certainly aren't regarded as sinful or vicious, but simple mistakes that any "flawed" human being (and who isn't that!) is apt to make now and then.

The Rule distinguishes between punishments requiring "the discipline of the Rule" meted out to monks who are deliberately or routinely disobedient or scornful of the Rule, and corrections described as "acts of satisfaction" prescribed for monks who make an error due to a lack of preparation, or because they weren't being attentive and careful.

As a frequent cantor at monastic liturgies, I have had to "kneel out" in the church many times over the years due to errors I've made intoning a hymn or a chanted responsory. And though kneeling down in front of the ambo as the community files past at the end of a service can feel humiliating, I also find it to be oddly gratifying too (weird, I know!). Taking the opportunity to exercise the discipline of admitting fault and holding oneself accountable to the community can gratify one's sense of integrity.

Sometimes, when I make a mistake - I break a dish in the refectory, lose a key, or scratch one of the cars pulling out of a gas station - I initially get upset and heap all sorts of insults at myself. Such self-derision isn't helpful and it doesn't nurture humility - in fact, it's the opposite. It's as if I am saying to myself, "You're flawless and perfect, so how could that happen to you?"

Humility is about standing in one's truth: "That happened because I wasn't paying attention; or because I was negligent and didn't prepare well; or because I was needlessly trying to be funny." The truth, not scorn, is the stuff of humility and my next thought ought to be: "It was my fault and I'd like to admit as much to the others."

Personal accountability promotes harmony and tranquility, and if community members generally refuse to acknowledge their own mistakes or faults, or if there is no means for them to do that, then resentment can build up among the members. This can lead to one of St. Benedict's least favorite things: grumbling.

The discipline of personal accountability is a must for the sake of harmony. To live in harmony with others, one must take responsibility for one's errors and mistakes and stand firmly in the truth. When done out of love for the community, the admission of fault results in a more tranquil and joyful disposition because it's rooted in personal integrity.

Benedict clearly wants the discipline of personal accountability to be instilled in every monk for the sake of a genuinely peaceful community life. As a principle of integrity, such accountability can increase the overall tranquility of an entire community, of a family, or any organization.